Zen for Film and the Discourses of Use Zen for Film and the Discourses of Use(a presentation on transcoded film for Peter Decherney's course Internet Policy and Culture)

|

|

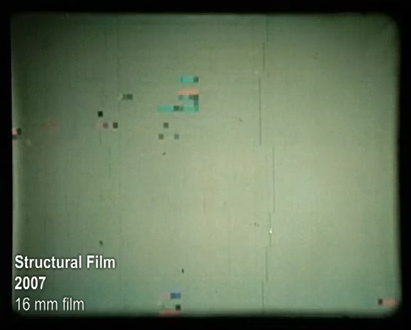

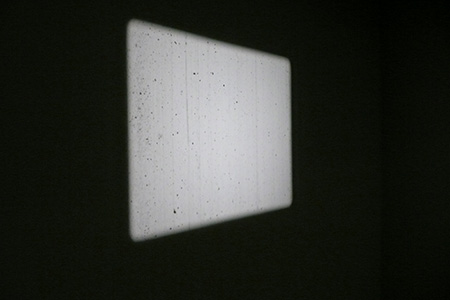

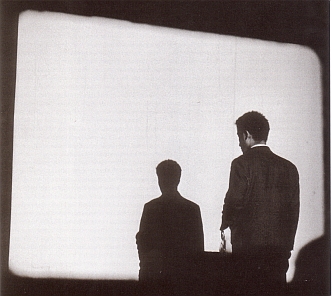

Research for a paper on the way historical art films have been digitized and dispersed online has led more often than not to incommensurate value systems, critical registers, and ethical ramifications. In an attempt to make some sense of the issues at stake for the array of intellectual communities thinking about this activity, I will be examining the digital remediation of Nam June Paik's Zen for Film in the context of a few key interpretive discourses, working through differences and resonances in interpretation. Taking the title of this course word by word, I'm exploring the heterogeneous and hotly contested connections between "policy" and "culture" on the internet through a single digital artifact. Just as the film is passed through a series of format shifts from celluloid to flash, I run Zen for Film through a series of interpretive filters: 1) Art Historical Criticism (appropriation, medium-specificity, conceptual art); 2) Film Restoration and Archiving (bio-fiction, classification theories); 3) Literary Media Theory (remediation, textual conditions); 4) New Media Theory (transcoding, technical digital properties); and 5) Law and Legislation (fair use, transformation, copyright). To begin, some functional vocabulary we haven't covered in class: Medium-Specificity and Media-Specific Analysis: popularized by Clement Greenberg regarding modernist art, though originally theorized by Gotthold Lessing and now pervasive in art criticism and practice, medium-specificity is notion that artworks ought to operate with "the distinct materiality of artistic media," manipulating those properties "unique to the nature" of a particular medium. By extension, N. Katherine Hayles calls for a media-specific analysis that "attends both to the specificity of the form...and to citations and limitations of one medium in another. Attuned not so much to similarity and difference as to simulation and instantiation, media-specific analysis (MSA) moves from the language of 'text' to a more precise vocabulary of screen and page, digital program and analogue interface, code and ink, mutable image and durably inscribed mark, texton and scripton, computer and book." (Clement Greenberg, "Modernist Painting" and N. Katherine Hayles, "Flickering Connectivities in Shelley Jackson's Patchwork Girl: The Importance of Media-Specific Analysis.") Remediation: Bolter and Grusin propose remediation as a "general theory of media" updating McLuhan's premise that "the 'content' of any medium is always another medium." Remediation is characterized by dueling processes of "immediacy" (representational transparency) and "hypermediacy" (the proliferation of media formats). (David Bolter and Richard Grusin, "Remediation" also see Matthew Kirschenbaum's critical review of the book length version.) Transcode: Manovich outlines how to "transcode something is to translate it into another format" specifically from old to new media "between the layers of the computer and the layers of culture." For Manovich, transcoding involves four other principles of the computerization of culture: "numerical representation," "modularity," "automation," and "variability." These principles together map some of the more important technical aspects of transformation when translating old media to computer networks. (Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media 27-46) Appropriation: "In the visual arts, to appropriate means to adopt, borrow, recycle or sample aspects (or the entire form) of man-made visual culture. The term appropriation refers to the use of borrowed elements in the creation of a new work[2] (as in 'the artist uses appropriation') or refers to the new work itself (as in 'this is a piece of appropriation art'). Art practices involve the 'appropriation' of ideas, symbols, artefacts, image, sound, objects, forms or styles from other cultures, from art history, from popular culture or other aspects of man made visual or non visual culture.[3] Inherent in the process of appropriation is the fact that the new work recontextualizes whatever it borrows to create the new work. In most cases the original 'thing' remains accessible as the original, without change." (Appropriation (art), Wikipedia) Supertemporal arts: a phrase coined by Lettrist filmmakers Isodore Isou and Maurice Lemaître in the 50s. The supertemporal work specifically includes the historical transformations of repeated use as part of the work. For film, these transformations include dust accumulation, scratches in the celluloid, damage to the film, future alterations, screening histories, and event attendance. Presumably, they might also include translation into new formats. (See Nicole Brenez, "Improvised Notes on French Expanded Cinema" and Maurice Lemaitre, Ever the Avant-Garde of the Avant-Garde till Heaven and After) Zen for Film (1964) as presented online by Kenneth Goldsmith at UbuWeb as part of the full Fluxus Films digital release in early 2006: Conceptualized by Nam June Paik in 1964, the film consists of clear, unexposed 16mm film leader to be played in a continuous loop for an unspecified amount of time (screenings range from 8 minutes to 60 minutes or more). A supertemporal filmic response to John Cage's 4'33", Zen for Film brings the materialities of filmic projection and historical transformation into the work itself, gathering new scratches and dust with each revolution through the reels and over time. Using Online 1: Art Criticism and Practice. The long tradition of appropriation in the arts approves any use that recontextualizes a previous work, especially if conceptualized as a new moment of authorship or highlighting an aspect of the work that was previously unnoticed. Photographers like Sherry Levine and Richard Prince have pushed the limits of 'un-creative' appropriation in photography, a tradition extending back to Duchamp if not before, to great critical acclaim. An art-historical or media-specific analysis of the digitized version of Zen for Film would highlight the aesthetics of digital authorship as a means of shedding light on new media networks. Already, a series of contemporary film artists have appropriated the concept and material for Zen for Film for a variety of purposes. (See below.) 2: Film Restoration and Archiving. Archivist have a long tradition of classifying modes of restoration and evaluating ethical approaches to the transfer of film to new formats. Dino Everett's typology outlined in his essay "Introduction to Bio-Fiction Classification Theory: Remix Methodologies and the Archivist" brings remix practices to bear on contemporary digital restoration strategies. The typology of classifications presented for digital remediation are useful for understanding to what extent the film is transformed. Embedding Zen for Film in the browser would waver between the most radical (least faithful) forms of repurposing: "performative-manipulative" and "confrontational-manipulative." 3 & 4: New Media Theory: Remediation and Transcoding. Using the terms described previously, remediation and transcoding respectively outline the translation from film to digital media. Operating on a more general, descriptive level of the cultural history of remediation on one and and the interface driving the computerization of cultural artifacts on the other, these works help to understand how Zen for Film fits within larger cultural and technical transformations. 5: Law and Legislation. Finally, the previous four filters allow a fuller exploration of the four considerations laid out by Leval in evaluating the fair use of the film online. Special attention is given to the issue of transformation. Recent rulings in Blanch v. Koons, Kelly v. Arriba Soft., Perfect 10 v. Google and the Betamax Case in conjunction with popularly published fair use guidelines and DMCA legislation also prove useful in mapping out the cultural implication of Zen for Film and other media-specific works digitized online. Uses of Zen for Film. Three significant artworks have been made using material and conceptual properties of Zen for Film. The previously accomplished filtered study of a digitized Zen for Film opens new considerations of these works, which in turn further reflect on Nam June Paik's original. Cory Arcangel, Structural Film (2007). The artist uses iMovie's aged film setting to create a born-digital version of Zen for Film, which is then transfered to 16mm. Glitches occur in the transfer which results in colorful pixelated debris. Mark Amerika, Zen for Mobile Phone Video (2007). Seeking to replicate the meaning of Zen for Film in a new media context, artist and writer Mark Amerika records his shadow on a projection of the film at the Centre Georges Pompidou with an extremely lo-fi mobile phone. Mungo Thomson, The Varieties of Experience (2008). Using an old print of Zen for Film, Mungo Thomson translates each frame to its negative for projection in 16mm and publication in book form. The new film preserves the dust accumulated in the original, highlighting flickering stars on black rather than dirt specks on white. Related Media-Specific Films. Zen for Film is only one instance in a long tradition of medium-specific, site-specific, conceptual, and structural films from the historic avant-garde up to the present day that has been remediated to the browser. While contemporary artists of the last thirty years or so have had to bear the possibility of new formats for their work in mind (conceiving work either in resistance or accommodation of new media formats), earlier filmic practitioners did not foresee the uses to which their films would be put. For further examples of films and moving image artworks that have been transformed by digitization, see works featured in two recent flash essays: "Flash Artifacts" (with Joao Enxuto, 2009) and "Although You May Start Out Looking For A Yellow Sky You May Prefer A Pink One Once You See It" (2010). A short, arbitrary, list would include: George Brecht -- Entrance to Exit (1965), Jack Goldstein -- MGM (1975), Standish Lawder -- Color Film (1971), Tacita Dean -- Kodak (2007), Marcel Duchamp -- Anemic Cinema (1926), Vito Acconci -- Theme Song (1973), Mauricio Kagel -- MM51 / Nosferatu (1983), John Baldessari -- Time/Temperature (1972--73), Richard Serra -- Boomerang (with Nancy Holt) (1974), Dan Graham -- Performer/Audience/Mirror (1975), Peter Campus -- Double Vision (1971), Paul Sharits -- Dots 1 & 2 (1965), Gary Hill -- Black / White / Text (1980), Hans Richter -- Rhytmus 21 (1921), bpNichol -- Word Pieces, Hans Richter -- Rhytmus 21 (1921), Jeremy Blake -- Century 21 (2004), Fernand Leger -- Ballet Mécanique (1924), George Landow -- Film In Which There Appear Edge Lettering, Sprocket Holes, Dirt Particles, Etc (1965--66), Stephen Dwoskin -- Dirty (1965), Anthony Balch & William S. Burroughs -- The Cut--Ups (1966), Ernie Gehr -- Shift (1972--1974), Michael Snow -- So Is This (1982), Tehching Hsieh -- One Year Performance, No. 2 (1980--81), Nam June Paik -- Beatles Electroniques (1966--69), Carolee Schneeman -- Fuses (1965), Joseph Beuys -- Filz TV (1970), Chris Burden -- TV Ad (1973), Stan Douglas -- Monodramas, "I'm not Gary." (1991), and Skip Arnold -- Punch (1992). Ultimately, the commingling of these discourses reveals a rich new perspective on transcoded film along with a strong argument for fair use of the digital archiving of media-specific works.

|