|

A flash artifact project in critical remediation by Danny Snelson

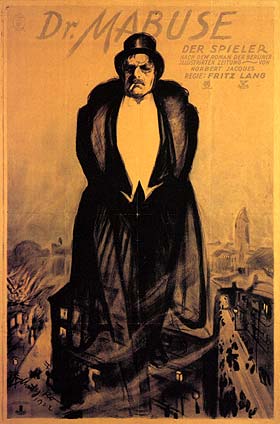

Situating the criminal mastermind of Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler within the webs of digital culture spun by contemporary technologies |

|

In Norbert Jacques' Dr. Mabuse, Lang found a character who could fully develop the issues of authorship and control in relation to the Destiny-machine through his mastery of a vastly radiating, and distinctly technological, web. Tom Gunning, "Mabuse, Grand Enunciator" from The Films of Fritz Lang The document Mabuse has produced forms a self-perpetuating machine that (re)creates its author in its reader. Mabuse doubles himself, and the text that makes this duplication possible leads a life of its own; the doctor's testament acts both as a means of spreading evil and as a way of obscuring its source. Erik Butler, "Dr. Mabuse: Terror and Deception of the Image" We observed that Mabuse's hand continuously made writing motions in the air, on the wall and on the bedspread. We gave him pencil and paper. At first, he covered the paper with senseless scribbling. Two years ago, however, several lines of code began to appear on the paper. Then whole clauses began to form, still meaningless and confused. Gradually they grew more coherent and logical, and at last we began to get glimpses into the extraordinary phenomenon that was his mind. His thoughts still move in the same digital channels as before. Whatever Mabuse writes is based upon incontrovertible logic and serves as a perfect guide for the commission of file sharing worked out in the minutest detail. Das Quelltext des Dr. Mabuse (subtitles) by giuliettamasina, YouTube, February 17, 2009 Strange how this name has become a symbol, how this mad manipulator of cards and fates has not been forgotten over the past ten years. Now he has reappeared. [...] Conquered at last, he has still escaped into an inviolability and we humans are resigned and powerless in the face of it: the tragedy of a fate ruthlessly fulfilling itself according to its own laws. Thea von Harbou, Berliner Tageblatt, No. 142, March 26, 1933 |

R e v e a l S o u r c e C o d e : Introduction, Watching Mabuse on

YouTube: Watching the clip "Dr. Mabuse, Ein Bild der Zeit [Part 1/13] (Fritz Lang,1922)," uploaded by a 21-year-old Romanian YouTube user operating under the alias xxPenumbraxx, I can identify with that vatic first scene: "HE and his day." After the clip loads its introductory information—quickly sliding the time bar past the slow progression of opening titles—the action opens on the hurried, though exacting, ornamental arrangement of a series of avatars, cascading like playing cards or user images in a pair of hands. Whose hands? The actor Rudolf Klein-Rogge, the director Fritz Lang, an unknown professional—there is no way of knowing.[1] After selecting eight possible identities—all that the screen can comfortably hold in its frame at one time—the image cross-fades to the blank-faced man sitting at his desk: the petit bourgeois antihero, Dr. Mabuse. The irising of the frame and the actor's peculiar gaze both remind us that he sits before an intricate technological apparatus throughout the scene; every action is staged for infinite reproduction.[2] Casually shuffling through this set of pre-determined identity masks, we already know that each anonymizing agent will be activated by contingencies at different sites in response to various schemes and protocols.[3] Following a cut back to the medium-shot of the desk, Mabuse randomly selects an avatar from this seemingly endless series of choices; chance operations are the best cloak for unpredictable attacks. Having made his selection, he automatically sends it off to an agent of his operating system: first betraying his composure as a neurochemical stimulant glitch slows down his social networking preparations. He is pained by any delay in transmissions. He threatens and curses the anonymizer application for freezing up, and irritatedly resends the identity masking information before turning his attention to a handheld device. The first parallel cut is unexpected and startling: sensational enough to keep my attention, for the moment.[4] As immediate as selecting another YouTube clip, the montage opens a window on a fast action locomotive sequence employing the three cinematographic stages of action—long shot, medium shot, close-up—first employed by the Lumieres' arrival of a train. Throughout the sequence Mabuse's eyes remain fixed to the small mobile device ticking away in his hand, as though it's streaming the moving image right from the palm of his hand.[5] The servers in his network follow the absolute control of an elaborate protocol worked out to the smallest detail: activating automobiles, rail systems, and telephone lines in concert with their perfectly synchronized mobile devices, each of which mirrors the streaming content of the filmic iris. Instantaneously, an interconnect operator transmits the encoded outcome of the criminal escapade, calling in with space-defying immediacy through a seamless network direct to Mabuse's desk. He receives the news with the boyish anticipation of a user refreshing his inbox. The thrill of the perfectly timed montage, the exacting speed of error-free protocol, and his flawless exploit of the system incites him to shout delightedly to himself while seated at the desk before the recording mechanism. Since the film is technically silent, (forgetting for a moment the high-fidelity, attention-grabbing soundtrack added to the film in 2001) we receive a text message instead: Bravo Georg'! Satisfied with the momentary novelty of this sensational sequence, he closes the line and returns to the routine demanded of a webmaster engaged in the constant maintenance of his criminal network... Watching this scene alongside windows open to PDF files by Gunning and Crary, isn't it clear that the protocological network is enunciating Mabuse and his off-screen doppelgaenger, the director Frtiz Lang—both materially and figuratively—and not the other way around? The spectatorial scenario I examine in this paper explores the thesis that in this thoroughly revised online context Lang no longer enunciates his will as published in 1922 and characterized by the figure of Mabuse, but is instead subsumed by the delirious logic of technological modernization and media historical circumstance.[6] Interlude, Transcoding

Cinema to the Console While the internet analogy in the

narrative above has been amplified for dramatic effect, the immediacy of the

scene remains allegorically robust, mutatis mutandis, for contemporary

viewers—5,168 of whom have seen this very clip streaming on their console

in the past year and a half.[7] Already in

1981, Noel Burch notices this remarkable phenomenon in his "Notes on Fritz

Lang's First Mabuse," finding a contemporaneity "confirmed

time and again on the occasion of student screenings in both Europe and

America. Whereas other key films of the period... appear to almost anyone today

as fundamentally archaic, Mabuse, though it may not seem as

stylistically modern as L'Herbier's l'Argent, for example, does seem amazingly

close to our own cine-dramaturgical space, owing to the

preciseness of its dramatisations, the subtleness of

its characterisations and the multi-layered density

of its script."[8]

The 'strategic position' that Burch locates in Dr. Mabuse is

marked by its uncanny ability to "address itself directly to 'us' today,

insofar as we are all 'average spectators.'"[9]

This paper asks, how exactly does Dr. Mabuse address itself to us

today, who directs the enunciation, and what does it mean to be an 'average

spectator' experiencing historical films digitized for computer screen? Rather

than cast off the widespread, and often criminal, practice of watching movies

online as an inconsequent derivative of cinema proper, I consider the digital

versioning of historical cinema as the widespread cultural activity it is, and

investigate the unique brands of versioning and authoring that occur via historical

and contemporary practices of dispersion and manipulation. It's curious that while excellent scholarly

work has gone into issues of content streaming, intellectual property, media remediation,

and remix culture vis-a-vis online movies and digital cinema, little to no

critical work has examined digital versions of complete historical films

trafficking online, much less the networked experience of viewing these films.

Whether this is simply the manifestation of a cinephilic

distaste for the degraded quality, distracted environment, and sketchy legality

of this activity or is symptomatic of a larger disciplinary blind spot

regarding issues of event specificity, popular distribution, and media

translation is beyond the scope of this paper. The fact remains that

increasingly substantial numbers of spectators experience digitized films on

their computers: streaming on sites like YouTube, UbuWeb,

and MegaVideo; purchased from iTunes

and NetFlix; or illegally downloaded from servers and

torrent trackers like The Pirate Bay, RapidShare, and

Karagarga. From the newest blockbusters to the rarest arcana,

today's users only express surprise or frustration when a title isn't immediately

available for streaming or download. With

a generation of spectators taking these conditions as a basic assumption, it

becomes increasingly pressing to question: what do these viewing experiences

mean? What are they watching? Who authors the cinematic experience when it

happens at the console, across a variety of platforms with limitless settings

and configurations? What does a user see when watching Dr. Mabuse stretched

out serially across thirteen YouTube videos?[10]

What happens to The Big Sleep when it's framed by an the easily manipulation

of a QuickTime player? Further, what do we make of more creative versioning

processes typified by revised subtitles and alternate soundtracks, or more

extreme manipulations such as remixes, datapours, or

recorded VJ screenings? Increasing numbers of viewers experience cinema in

these ways: how do we reconcile historical authorship functions with the daily

practice of online entertainment systems? While auteur theory uniformly looks backward to the production and release of the film, today's radical remediation of cinema makes it as necessary to carry the same concerns forward to later versions and contemporary techniques of spectatorship. Nevertheless, it remains essential to return to critical sources like Andre Bazin, whom, in La Politique des Auteurs, writes: "So there can be no definitive criticism of genius or talent which does not take into consideration the social determinism, the historical combination of circumstances, and the technical background which to a large extent determine it."[11] Under a delirious logic of remediation, where transcoding and distribution processes radically transform the original film, we can begin to ask how these social, circumstancial, and technical determinants of the cinematic object might supersede the agency (or agencies) directing the original production. I. Authoring Mabuse As a test case, I have downloaded, segmented, uploaded, embedded, and networked Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler: Ein Bild der Zeit, within the very systems I investigate.[12] The powerful figure of Mabuse, built through the history and narrative of the film itself in conjunction with the rich critical discourse surrounding the film will thus provide a cipher to decode some lines in the impossibly complex webs of versioning, online dispersion, and remediated authorship. Critical scholarship agrees: Mabuse stands as the paradigmatic master enunciator of modern technology, the exploits of his system figure those of the filmic director and the cinema at large. As Gunning argues, "Lang creates not only his ultimate figure of urban crime, but his most complex enunciator figure, the author of crimes who aspires to be a demiurge in control of his own creation, Lang's doppelgaenger as director and author who will haunt Lang for nearly the full extent of his career."[13] A fact we have known since 1933 with the gramophone of Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse and the televisual surveillance of 1960 in Die tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse, though also clearly manifest in the silent films of 1922, the Mabuse figure has also always been a metonym for the shadow side of new media and modern technology. As Jonathan Crary writes: "What becomes clear is how the name 'Mabuse' does not finally designate a fictional character that Lang returned to several times. Rather Mabuse is the name of a system—a system of spectacular power whose strategies are continually changing but whose aim of producing 'docile' subjects remains relatively constant... In the first of these films, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, Lang sketches out a panoply of modern practices of control, persuasion, and coercion."[14] Mabuse thus haunts every new media as a maniac specter, exploiting the fissures of excessive capital to harness the technical logic of the systems facilitating his anarchic control. Extending this archetypal figure for both filmic auteur and technologist to the fast-changing terrain of digitized cinema in the YouTube era, we find that what Mabuse expresses in every new digital version or streaming format is nothing less than the authoring determinacy of networked media itself. Mabuse, seen as the technologized Grand Enunciator, is precisely the myriad components of HTML protocol, GUI software, and networked hardware that facilitate the spectatorial environment. More generally, through Dr. Mabuse we are able to chart the ways in which cinematic authorship go insane: Mabuse is no longer a character in a film, but a maleficent current reconfigured by the very networks it inhabits, a ghostly repossession that replaces Fritz Lang as the author of the digital object. Slipping through the hands of director and medium, Dr. Mabuse falls to the editorial power and functional authority of anyone with a console connected to the internet. Exercising full control over digital objects in terms of segment cuts (often exhibited in multipart series due on time limitations), production values (from contrast or color ratios to variable compressed encoding values), distribution (on torrent sites, sharing communities, and public databases) and contextual location (clips are strung together, responded to, deleted, resurfaced, tagged, introduced, and commented upon)—historical films streaming online are authored by multivalent users plugged into the tangled networks of versioning and protocol governing digital remediation. Effectually 'photoshopping' Lang's hand out of the picture through these alterations, digital functions return us to Foucault's advice to "reexamine the empty space left by the author's disappearance; we should attentively observe, along its gaps and fault lines, its new demarcations, and the reapportionment of this void; we should await the fluid functions released by this disappearance."[15] Digital media brings this waiting to an end: producing a "fluid text" constantly in flux wherein the hard and fast lines of a text subject to functional human authorship are washed over by unseen numbers of actors—man, hardware, and algorithm—handling media objects in ways unfathomable in pre-digital epochs. Throughout these processes, we need not forget the history of the film. A simple Wikipedia search brings the full historical details of the film production into focus, and a few more Google searches can access the rich critical commentary—on the film or the studio, on Fritz Lang, Thea Von Harbou, or any of the actors, on its historical reception and context—in PDF articles or full books by scholars like Tom Gunning, Noel Burch, David Kalat, and so forth. However, in the place of reading the digital object as a deictic index for some previous filmic experience or rehashing the old narratives of a time almost a century removed, we can shift figure and ground to open a new window on authorship under the logic of cultural remediation. Why not embed the robust critical discourse surrounding Dr. Mabuse as a means to refresh our study of its digitization? As a figure for the cinematic author par excellence, a networked Mabuse can thus bridge historical cinema and auteur theory with contemporary media and transcoded authorship. Reading the digital object Dr. Mabuse as witnessed online, we can thus readdress the figure of Mabuse in an attempt to produce an approach to cultural artifacts in a time of radical dispersion. This paper thus surveys the uncanny applicability of Mabuse's criminal network to internet culture, charting the ways in which the figure haunts contemporary technologies, and how this new situation alters the authorship of the film in return. First, the history of the film itself reveals a wild tale of manipulative versioning: from Fritz Lang's obsessive edit to the variously altered international releases, the digital reconstruction efforts and subsequent studio releases, and user-generated online dispersion. Then, considering scenes of disguise, control and protocol, hidden spaces, gaming, counterfeiting, and mass hypnosis, a reading of Dr. Mabuse through the browser will reveal layers of allegorical anticipation on every level. Finally, these explorations will argue the film provides a compelling entry point into fundamental questions of forensic materiality and distributed authorship—an endless mise-en-abime not unlike Mabuse's ever changing identity masks. As McLuhan so clearly envisaged, the content of a digitized film can only be the character of digital technology itself: this paper contends that this character is best played Mabuse, a robust object of study for cinema troubled by chaotic processes of modernization.

II.

Who Is Behind All This? From its initial release in 1922, a coherent document entitled 'Dr. Mabuse' is destabilized as the dubious remnant of historical lapses and dispersed versioning processes—an action traceable right to the opening sequence of its first screening. Originally screened in two parts at the Ufa Palast am Zoo in Berlin, Decla-Biskop's marketing scheme for the epic Dr. Mabuse der Spieler presented the film in two parts—Part I: Der Grosse Spieler: Ein Bild der Zeit (April 27, 1922) and Part II: Inferno: Ein Spiel von Menschen Unserer Zeit (May 5, 1922).[16] Lang's story of the original screening, canonized by numerous critics through Lorre Eisner's book Fritz Lang, recalls this first version opening with "a brief, breathless montage of scenes of the Spartacus uprising" followed by two intertitles—"WHO IS BEHIND ALL THIS?"—answered by a single word growing to fill the screen—"I."[17] The vibrant political scene is nowhere to be found and perhaps Gunning is correct in doubting its very existence. [18] The author's recollection relayed to Eisner is in all likelihood another Langian memory lapse. However, this oft-repeated anecdote—a political revision not entirely unlike Lang's Nazi-horror Goebbels story—has become as much a part of the film's bio-fiction as any frame.[19] For example, the spectral presence of the anecdote highlights the political efficacy of Georg's suicidal Goethe quotation or the rebellious charge of Mabuse cursing von Wenk, the 'bloody hound.'[20] Real or invented, once invoked, the ghost of this potential opening scene has a very real impact on the experience of the film. From the beginning, there is no empirical way of knowing what any 'primary' spectator fully experienced in the screening of the authorial cut of Dr. Mabuse released in 1922. Better known is the trail of international distribution, including the variously mangled French, Italian, and British versions, all released a year after the German screening in 1923. The French version cut the film down to 205 minutes, the Italian to 213 minutes, and the British to 217 minutes from what is assumed to be 297 minutes of original footage.[21] Some five years later in 1927, the American release aggressively cut the epic 217-minute British version down to an easily consumable 97 minutes.[22] These various circulating versions translated more than just the look and content of the film's intertitles—each new version was re-cut by local editors for their respective national viewing environments. While an extensive comparison of all these international versions is clearly beyond the scope of this paper, a hint of the widely changing plot and reauthoring processes can be drawn from the wealth of titles introduced by international distribution; from The Fatal Passion of Dr Mabuse to Dr. Mabuse King of Crime, to the grossly transformed Gilded Putrefaction—the little-known Soviet version re-edited by Esther Shub and her young apprentice Sergei Eisenstein.[23] Each new national aperture refocused the film according to a variety of editorial and interpretative translations. However, it would be generally accepted that all, or most, are versions, perhaps with degraded authority, of the 'Fritz Lang Film.' As I'll argue throughout this paper, while the viewing environment and 'user-generated content' formulated in the diverse processes of distribution and remediation grows increasingly more authorial as the history of Dr. Mabuse moves further and further from the director's hands, a material approach to historical editorial processes already reveals an authorship function stretched to the limits of applicability. Following

these degenerative international releases of the twenties, and a resultant

array of VHS and DVD transfers in the eighties and nineties, a 229-minute English

version was reconstructed by David Shepard for the

Image Entertainment distributor in 2001,[24]

which seemed definitive prior to Transit Film's restoration released in 2004,

bringing 270 minutes together in an 'authorized' edition.[25]

As the DVD notes: "Restoration and

reconstruction took place in 2000 as a co-operation between the film archive of

the German Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv),

Berlin, the Filmmuseum Muenchen,

and the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, Wiesbaden.

The present version follows a copy compiled by the Filmmuseum

Muenchen from the two mentioned negatives and a copy

of the Gosfilmofond film archive in Moscow."[26]

Compiling three filmic sources and a variety of digital filters as well as

adding a new score composed by Aljoscha

Zimmerman, the now-standardized DVD follows a hybrid "performative-manipulative"

restoration strategy, dramatically altering the film to optimize its

performance for contemporary audiences.[27]

While attempting to replicate the original, the Transit released DVD produces

an entirely new work performing accepted scholarship for contemporary

audiences, complete with extras and potential voice-over tracks. As Sean Cubitt notes in "Codecs and Capability," the moving image

accumulates the debris of its various compressions, cuts, and formats,

oscillating from the DVD transfer, fetishizing the filmic artifact with all its

scratches and imperfections in a "sublime" high resolution, to the lo-res

YouTube streams, which replace the filmic with blunt pixilated digital

artifacts all their own.[28] Further,

this corporate-institutional digital reconstruction renewed an interest Dr. Mabuse, opening the door to illegitimate

dens of online trafficking discussed below. III. Das Quelltext

de Doktor Mabuse On Christmas Eve, 2004, at precisely 16:11:58 GMT, the Pirate Bay user Beat may have been the first to openly upload the entirety of Dr. Mabuse as a torrent to the internet. Then, on July 21, 2005, Cocteau uploaded the British intertitle version of Dr. Mabuse to the invitation-only, international private torrent tracker Karagarga. In 2010, two additional digital versions of the film were added to Karagarga: the first version by Jurgeen distributed by MK2 in France, while the other by airneck featured the Masters of Cinema Eureka packaged disc. Ranging in size from 1.37GB to 13.89GB, each version varies in terms of encoding quality, brightness, frame rate, and frame size. Many more versions traffic online, currently seeding through torrent indexes such as ISOHunt, TorrentReactor, and The Pirate Bay. The details are hazy at best and in many cases impossible to locate. Some users have since logged out of their communities, several versions are uploaded anonymously, while unknown numbers of uploads or sites have been deleted or removed. Although presented in any number of locations across an array of platforms, each of these avatars mask the identity of a information distribution agent claiming to be offering a legitimate Fritz Lang film Dr. Mabuse. However, the control each user and piece of software exercises over their stolen upload—ripping from an already modified cassette or DVD, pushing that capture through codecs, cutting the resultant object into segments for size and length, adjusting RGB, contrast, frame rate, and a variety of major alterations—further wrests the delicate authorship from the original film, as digital artifacts, editorial decisions, and reprocessing algorithms accumulate. Indeed, the catch and release of information is described by Gunning as a key component of the symbol of authorship presented in Dr. Mabuse: "theft gives him control of information. Like a skilled author or dramatist, Mabuse asserts his authority by managing information, first witholding it, then releasing it at precisely the most effective moment."[29] The digital capture and processing of film followed by network dispersion endows the same level of authority to each user and the information systems that determine the management of dispersion. Alongside these full film torrent uploads, Dr. Mabuse has streamed in clips, remixes, and dramatically modified versions on flash-based movie sites Vimeo and YouTube. We began the paper with YouTube user xxPenumbraxx's full Dr. Mabuse upload, ripped from the old British intertitle format distributed by Kino, streaming through 13 inter-linked segments: a degraded form that bears as little formal resemblance to the Fritz Lang film as a 200px thumbnail image in a search engine to a 20 inch photographic print in an art gallery. Later that year, the Brazilian user flaviosunpin re-cut and uploaded the entire film with Portuguese subtitles to YouTube. Meanwhile, users ZioBurp (in 2007) and jsantiagot (in 2009) have uploaded alternate soundtracks cued to footage from Dr. Mabuse. Cartoon versions have been drawn while several users across a wide range of platforms take some variant of Dr_Mabuse as an avatar, often with an icon from the original film. Trailers and movie reviews cued to posters, clips, and other ephemera are uploaded frequently. A few months later, kitanoita uploaded a remix of the French version of the film, publishing an entirely new montage of Dr. Mabuse footage cued to the beats of a dark wave minimal synth tune called "New Moon Rising" by Wolfmother, crafting a new narrative of lusty bourgeois techno-hedonism not dissimilar to the ideologically reauthored plot of Gilded Putrefaction. As the versions proliferate, with orphaned footage altered in terms of montage, soundtrack, media format, image quality, and contextual location, the author's functional "means of classification" is both diminished by the network and augmented by the need to categorize all this diverse activity.[30] Foucault posits "the name of the author remains at the contours of texts—separating one from the other, defining their form, and characterizing their mode of existence."[31] However, when the contours of texts are no longer discernable amid these various transformations, it becomes impossible to separate, define, or characterize in terms of a single author alone. Instead, like any good web crawler or search engine, the digitized film can only be cataloged in terms of its interconnections and transformations by describing the technical network that defines its differential position. IV.

Multiples, Ghosts As though in anticipation of these versioning processes, the narrative arc of Dr. Mabuse continuously operates along a trajectory of multiples, from the opening array of Mabuse's disguises to the duplication of bodies as ghostly apparitions. Opening with the giant shapeshifting head of Mabuse hovering over the conquered stock market in part one, act one, and extending through Mabuse's mystical 'psychoanalytic' lecture producing an entire caravan a la Melies in part two, act five, the phantasmal reduplication of figures in every instance signifies the filmic power to manipulate the singular (or analog) diegetic reality of the mise en scene. The spectator discovers hidden contracts and psychological revelations through the magic of film superimposition, achieved by duplicating a fixed shot while displacing only the active agent, then layering the footage to include the new actor. While special effects accumulate throughout Dr. Mabuse, ghostly duplication plays a dominant role in the sensational narrative. While it is originally Mabuse's great power to alternate identities that allows him to exploit the anonymous modernity of Weimar Berlin, where anyone can access hidden domains with the right password and class encoding, his system of auto-reproduction is eventually driven mad when confronted by the spectral return of characters destroyed in the technically mediated progression of a story beyond his control. Sequences depicting Count Told's hallucinatory demise under the influence of Mabuse, beginning in the final act of part one, for example, speak from beyond the silver screen to this loss of control and issues of versioning through the browser. After securing an invitation through hypnosis during a seance, Mabuse infiltrates an evening party at the Told residence, with schemes to steal the Countessa Dusy Told and discredit her husband. Entering a chat with the Count and his friends, the doctor is asked for his opinion on Expressionism. He famously responds: "Expressionism is just a game, but, nowadays, in life everything is a game." The great Spieler naturally sees through claims of authenticity, singularity, and intensity in artistic expression; the Expressionist rendering of Lucifer above the Count's fireplace is just as constructed as the framing of the shot of Klein-Rogge scheming beneath it in the direct line of vision of the figure. Proving the power of his convictions, Mabuse steers the weak Count to an ill-fated game of poker, gazing from a position of surveillance with the already-stolen Countessa. While the entranced Count is caught manipulating the deck, the audience is treated to a close-up of the deck in the Count's hands artlessly flipping the top card to the bottom—"Falschspieler—!!"—and the crowd departs. Indeed, the cards were stacked against the convinced aesthete as Mabuse's technological destiny machine had determined the game from the beginning. Mabuse's Count attempts to keep a card, like a frame of celluloid, to himself, but we the audience like the guests in attendance aren't fooled by the selfish endeavor: the Count controls neither his movements nor the materials on screen. Beyond Mabuse's control, however, the digital reproduction of this scene introduces an effect film archivists call "ghosting."[32] As the puppet Count furtively shuffles the deck, a close-up of the mesmerized hands reveals a magic trick: the card in question literally disappears for a moment. Using digital filters that capture movement rather than each independent frame in a film, objects in rapid motion can easily disappear in transition, leaving only a transparent blur of pixels in their wake. Here, the cards are quite literally out of the Count's hands, and Mabuse's too, for that matter. Where a film still can discover a horse in flight, the frozen digital remnant points only to dead media returning without material body, at a loss for original intention. Mirroring the opening scene of absolute directorial control of identity cards, the digital disappearing act of this fated card metonymically figures the loss of enunciatory power in the film on every level. Reduplicated by any number of moments in the digitized film, a close reading of "Dr. Mabuse" online reveals a revised message of remediated symbols and transcoded allegories in the insane context of unforeseeable transformation. Lang, like the Count, is cheated out of his self-expression and authorial control by the unstoppable force of digital manipulation under technological progress. Only ghosts remain: each haunted moment bears the traces of an artifact that has ceased to signify outside the medium of its production. The insanity of filmic haunting continues for the ruined Count at the conclusion of part two, act three, as he returns to the fixed card table after weeks of drunken isolation under Mabuse's orders. Turning from the liquor cabinet the Count is transfixed as a transparent image of himself cross-fades into ghostly existence, superimposed on the screen seated at the card table opposite the Count's unwitting transgression. A technique first used in 1898 by G.A. Smith in The Corsican Brothers and popularly exploited by George Melies a few months later in his l'Homme de tetes, the superimposition of film is historically bound to scenes of impossible duplication in the service of the supernatural, the visionary, and the insane. Count Told's hallucinated ghost, shuffling a fixed deck of cards, is thus shuffled into the sequence of frames as a spectral representation of illusionary reproduction: a sign of the Count's madness, a filmic artifact hovering in duplicate twice removed from reality, and a representative of Mabuse's fixed deck destiny machine. As the scene follows a classic Svengali card trick, every selection by the shattered Count reveals the card not seen in the digital sleight of hand previously described—the ace of hearts. After establishing the inflexible destiny of the weighted deck, the card wielding ghost of Told is multiplied around the table to five specters surrounding the rapidly deteriorating 'real' Count Told. The six layers of film clustering around the table skip irregularly due to projector inconsistencies: the scene is literally trembling in the wake of filmic layering, the 'real' Count is outnumbered and overpowered by the manifold ghostly versions confronting him. Chased by this band of spectral reproductions through his house, the count throws light (a candelabra) in futility before collapsing to the still shuddering floor, his suicide at Mabuse's behest shortly forthcoming. Mabuse, the unstoppable force of technological modernization, infiltrates the Count's house for one last visit, this time under the pretence of psychoanalytic doctor, keeping the Count under counsel after stealing his wife. Informing the broken Expressionist aesthete that he is bound for the madhouse, Mabuse proclaims "Ihr Dasein ist vernichtet . . . Sie koennen nicht mehr leben . . . N i c h t m e h r l e b e n — — — !!" We are told even while staring at the digital image of the Count: his existence—ontological, allegorical, and narratological alike—is destroyed by Mabuse's systematic manipulation. Cannot live anymore, cannot live anymore, he repeats to himself in a trance on the way to a final cut, delivered by his own hand—the last flicker of life has in fact long gone out with the old reels. Self-control and authorial expression are eliminated under the progressive system of media modernization. We can perform a postmortem analysis according to Saint Jerome's four attributes of authorship as laid out by Foucault: "the texts that must be eliminated from the list of works attributed to a single author are those inferior to the others" (here the standard level of quality is entirely lost from celluloid to YouTube); "those whose ideas conflict with the doctrine expressed in the others" (any interpretation of the digital object directly conflicts with the original intent of the film); "those written in a different style and containing words and phrases not ordinarily found in the other works" (re-written by code, the pixelated artifact introduces its own vocabulary and stylistic register); "and those referring to events or historical figures subsequent to the death of the author" (everything from the comments framing the flash embed to the overlay of related clips following every segment points to the immediate present).[33] Mabuse's triumph cannot last, however, the Count returns along the rest of the rootless dead, driving the grand enunciator over the edge of sanity in concert with the self-perpetuating mechanisms and chaos-generating programs of a system "ruthlessly fulfilling itself according to its own laws."[34] V.

Conclusion: Mabuse's Final Abstraction In the concluding scenes of the film, Mabuse is finally defeated by the rigorous protocols of his own programming, which operate in seamless conjunction with the maddening return of former agencies crushed under the hand of Mabuse's technological gameplay. Narrowly eluding Von Wenk and the military troops assailing his estate, a battered Mabuse inadvertently locks himself into a subterranean counterfeiting lair designed to trap four 'blind ones' endlessly sorting and counting Mabuse's counterfeit bills like so many ISPs blindly transferring illegal packets along the network. Faced with failure and imminent capture, his hold on reality fades as the blind ones suddenly assume the ghostly doubles of those destroyed by his system, including Count Told and three others cheated out of their agency by the grand manipulator. A ghostly Count Told, fading in as embedded in Mabuse's psyche, now holds the cards, inviting Mabuse to the table for a final hand with the specters of analog reproduction. Atop the now-worthless forgeries, Mabuse deals himself a couple of aces, but this time he is called out—Falschspieler!—as the typography of the intertitle mirrors the delirious logic of the scene. The cards of fate have fallen from Mabuse's hands; his power to enunciate is eliminated by the system he once exploited. Driven mad, wildly throwing the worthless paper into the air, Mabuse is translated into pure abstraction: inscribed like a malicious virus into the films to follow (returning as a code exploiting the doctor of his insane asylum in Das Testament de Dr. Mabuse, 1933, and as criminal file programming the manipulative power of televisual surveillance in Die 1000 Augen des Dr. Mabuse, 1960,) as well as the digital afterlife of the film itself. What is this final insanity but an anticipation of Neo's absorption at the conclusion of The Matrix? Mabuse is fulfilling his role in the destiny machine of modernization. His former subject, the counterfeiting printing press, is animated as a terrible beast of virtual simulation. In his torment, Mabuse transcends the embodiment of old media and his former exploits to join the monstrous forces of technical contingency. As Gunning writes, "like the vision scene of Moloch in Metropolis, it also puts a face to the system, marking Mabuse as the demon of abstraction, disguise and control — of modernity.[35] Like the ghosts that surround him, Mabuse's insanity brings him into an ethereal realm of abstracted immortality, where his character is but one current in the delirious logic driving the determining systems of advancing technological power. If the auteur is "a subject to himself... someone who speaks in the first person," and the "I" directing the action opening the film is the figure of Mabuse standing in for Lang, then this final scene translates that former first person into an uncanny third person: the terrible and contingent logic of technological progress.[36] Amplified by the browser though latent in the film itself, Dr. Mabuse reveals the source code for a program by which authorship is driven insane over time through the relentless feedback loop of dead media haunting new media contexts. [1] Lang's repeated anecdote that his hands appear in every film stirs a hermeneutics of suspicion: every hand close-up potentially belongs to the director. The anecdote alone compromises the allegorical stability of even this first shot: already, from the first image, the paramount figure of authorship is distributed among a variety of potential sources. [2] The chaos of this reproduction is perhaps foreshadowed by Siefried Krakauer's influential thesis on circular figures in Mabuse, which we can extended to the circular iris enveloping many shots within the film. An artificial effect that highlights the filmic lens simultaneously prefigures the chaotic digital currents that spin the film around while remaining within the film's historical vortex. "The circle here becomes a symbol of chaos. While freedom resembles a river, chaos resembles a whirlpool. Forgetful of self, one may plunge into chaos; one cannot move on in it." Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 74. [3] Contrary to Kracauer's influential hypothesis, Jonathan Crary argues for Mabuse's anticipation of a society of biopower and pervasive control, "the protean Mabuse, in his multiple masks and guises, becomes a principle of flexible and versatile power rather than a figuration of totalitarianism." Jonathan Crary, "Mr. Edison and Dr. Mabuse," in Hall of Mirrors: Art and Film Since 1945, ed. Kerry Brougher and Jonathan Crary (Los Angeles, CA: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1996), 272. [4] There are numerous theses concerning new media entertainment systems and "sensation films" like Dr. Mabuse, particularly with regard to markets of attention and distraction comprising contemporary spectatorship. See for example, the collection of essays in The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, ed. Wanda Strauven (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006) and Joost Broeren, "Digital Attractions: Reloading Early Cinema in Online Video Collections," in The YouTube Reader, eds. Pelle Snickars and Patrick Vonderau (Stokholm, Sweden: National Library of Sweden: 2009). [5] "His eyes remain riveted on the watch as if it enabled him to see the scenes we have just witnessed thanks to parallel editing... Mabuse's criminal conspiracy is less an anarchistic threat to order than a parasite dependent on the systematic nature of modernity." Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity (London: British Film Institute, 2000), 97. [6] Studying Dr. Mabuse in this way extends Crary's argument that the film is "embedded in a rhythm of adaptability to new technological relations, social configurations, and economic imperatives. What we familiarly refer to as film, photography, and television are transient elements within an accelerating sequence of displacements and obsolescences, within the delirious logic of modernization." Crary, "Mr. Edison and Dr. Mabuse," 264. [7] Retrieved from YouTube page: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OGVg-Oi719Y&feature=related. When I began this paper in March of 2010 the clip boasted only 1,307 viewers—more than doubling in viewers over the last five months. Of course, this is only one page among innumerable options for viewing the sequence online. The clip was added February 13, 2010, and as of this moment has not yet been taken down for breach of copyright. There is no telling how many previous uploads have been removed. [8] Noel Burch, "Notes on Fritz Lang's First Mabuse" Cine-Tracts 4, no. 1 (1981): 1-2. [9] Burch, "Notes," 1. [10] An anonymous reviewer of Dr. Mabuse for the August 9th issue of the New York Times anticipates this logical extrapolation of the film to segmented YouTube uploads in 1927: "It is something like a serial posing as a mystery play." Anon, "The Crooked Hypnotist," in Fritz Lang: A Guide to References and Resources, ed. E. Ann Kaplan (Boston, Mass: G.K. Hall, 1981), 147. [11] Andre Bazin, "La Politique des Auteurs", in Auteurs and Authorship: A Film Reader, ed. Barry K. Grant (Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub, 2008), 22. [12] Providing an active supplement to this paper, I invite the reader to explore the site: http://aphasic-letters.com/mabuse. Undoubtedly a criminal criticism, the version of Dr. Mabuse used in this project was downloaded from Karagarga user airneck's excellent rip of the Masters of Cinema 2004 release of the Transit restored DVD. While I'm tempted to say this venture simply translates a version of an already popularly accessible movie from one format to another, there's no denying a Mabusian complicity. Where Mabuse plays with the release of a Cocoa contract to gain capital from the disruption of the German stock exchange, I'm here playing with the release of a digital object to gain cultural capital from the disruption of the cinema studies critical exchange. [13] Gunning,

Films of Fritz Lang, 96. [14] Crary, "Mr. Edison and Dr. Mabuse," 271. [15] Michel Foucault, "What Is an Author?" in Theories of Authorship: A Reader, ed. John Caughie (London: Routledge, 2005), 282. [16] Kaplan, Fritz Lang, 37. [17] Lotte H. Eisner, Fritz Lang (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 59. [18] Gunning, Films of Fritz Lang, 97. [19] The term bio-fiction is used by film restorationists to specify source material for the various processes involved in the reconstruction and manipulation of historical footage. See Dino Everett, "Introduction to Bio-Fiction Classification Theory: Remix Methodologies and the Archivist," The Moving Image 8, no. 1 (2008): 15-37. [20] Both references, otherwise enigmatic, have been shown to carry significant allegorical potential in reference to the Spartacus uprising. See Gunning, Films of Fritz Lang, 97-98. [21] Kaplan, Fritz Lang, 36-41. [22] While ostensibly cut as a more appealing cinematic commodity, The Fatal Passions of Dr. Mabuse, based on a poor British translation and completely manipulating the story line obviously failed. Losing the plot and suspense along with the length, reviews from the American release note how the dramatically recut film is actually slower, the re-edit boring and nonsensical. For example, an anonymous New York Times (August 9, 1927) review "The Crooked Hypnotist" writes: 'Dr. Mabuse' is far too long even as it is, and it has been cut down several reels... It looks to be about ten years old when one considers the acting and the verbose intertitles, which, incidentally, were written in England. Eighty-six of these captions were eliminated for exhibition here, but there still remain about 150, the usual number for a feature film. The dramatic revisioning of the American version can be seen in comparison to the reviews from the German release, for example Neue Zeit (May 4, 1922) writes: Speed, horrifying speed characterizes the film. The incidents chase one another. This is the present, the hustle and bustle of its life-style. Kaplan, Fritz Lang, 147, 151. [23] Recent study has gone into the dramatically altered Shub-Eisenstein remix of Dr. Mabuse released as Gilded Putrefaction. This paper includes an original translation from the Russian by Mashinka Firunts of the only essay available on this lost artifact. It can be found here: http://aphasic-letters.com/gilded-putrefaction.html [24] Mark Bourne, "Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler," The DVD Journal (2001): http://www.dvdjournal.com/reviews/d/drmabuse.shtml [25] Extensive comparison of the encoding stats of the two major distributions of Dr. Mabuse (the other distributor, Kino, has since taken the Eureka distribution version) can be found on DVD Beaver. See Gary Tooze, "Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler - Image Entertainment - Region 1 - NTSC vs. Eureka - Region 2 - PAL - DVD Review," DVD Beaver, http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film/DVDCompare2/drmabusegambler.htm [26] Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler, (London: Eureka Entertainment Ltd, 2009). [27] Everett, "Introduction to Bio-Fiction Classification Theory," 32. [28] Sean Cubitt, "Codecs and Capability," in Video Vortex Reader: Responses to YouTube, eds. Geert Lovink and Sabine Niederer (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2008), 45. [29] Gunning, Films of Fritz Lang, 102. [30] Foucault, "What Is an Author?" 284. [31] Foucault, "What Is an Author?" 284. [32] Noted in every DVD review, the digital transfer of Dr. Mabuse is "plagued by prevalent ghosting and combing." Keith Uhlich, "Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler," Slant Magazine, July 18, 2006, http://www.slantmagazine.com/dvd/review/dr-mabuse-the-gambler/967. See also Tooze, "DVD Review." [33] Foucault, "What Is an Author?" 287. [34] Thea von Harbou, Berliner Tageblatt, no. 142, March 26, 1933, in Kaplan, Fritz Lang, 41. [35] Gunning, Films of Fritz Lang, 103-104. [36] Bazin, "La Politique des Auteurs," 25. |